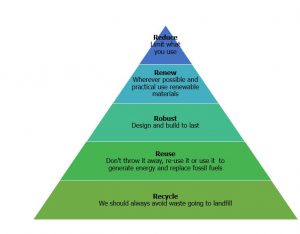

What is the circular economy?

“A circular economy is an alternative to a traditional linear economy (make, use, dispose) in which we keep resources in use for as long as possible, extract the maximum value from them whilst in use, then recover and regenerate products and materials at the end of each service life.”

Despite its current status as one of manufacturing’s pre-eminent buzzwords, the concept of the ‘Circular Economy’ has been around since at least the 1970s. It has been proposed as a solution to local and national resource security/scarcity issues and as a way to reduce the environmental impacts of our production and consumption, through methods including designing out waste, disruptive innovation, new leasing models and the use of renewable materials.

Adopting a circular economy system has a strong economic case and it is manufacturers that are most likely to reap the benefits quickest given their reliance on raw materials. Under WRAP’s Circular Economy 2020 Vision, the EU could benefit from an improved trade balance of £90 billion and the creation of 160,000 jobs. McKinsey has speculated that the EU manufacturing sector could realise net materials cost savings worth hundreds of billions per annum within the next 10 years. In short a more circular economy can deliver a more competitive UK economy, and further opportunities for growth.

Why is wood the material choice for the circular economy?

Energy and material from renewable sources

Any system should ultimately aim to generate energy through renewable sources. Needing little more than sunlight and rainfall to grow, producing timber requires significantly less energy than any other mainstream building material. For example, producing steel requires many more times the energy needed to produce wood; while concrete can give off 140kg CO2 per cubic metre produced. As a result of its versatility, timber is capable of displacing energy intensive alternatives and reducing pressure on the grid.

Simply growing trees is good for the environment, but in the UK the environmental benefits are greatly enhanced. According to the Timber Trade Federation’s latest annual report on Responsible Sourcing of Timber in the UK, of all TTF members purchases, 91% were from certified sustainable sources and only 1-3% were from high risk sources where members have worked to put in place their own risk mitigation measures.

Sustainable forestry ensures that the process of CO2 absorption and oxygen emission is maximised. Trees are sustainably harvested at the peak of their cycle, and replaced with younger, more carbon efficient trees, before their ability to absorb and emit declines.

Reducing harmful waste

Within a circular economy, the biological and technical components of a product must fit within a materials cycle, designed for disassembly and re-purposing. The biological nutrients are non-toxic and can be returned to the cycle. Technical nutrients – polymers, alloys and other man-made materials are designed to be used again with minimal energy.

Timber is renewable and it uses low energy processes and generates little waste that cannot be recycled or used as a source of renewable fuel.

With the amount of wood waste declining since 2009 and the volume of material ending up in landfill much smaller than originally thought, today’s joinery products can be recycled or disposed of in a sustainable manner when they reach the end of their life. There are also economic and sustainability benefits facilitated by recycling wood so that it could be used by important value-adding manufacturing industries.

Wood waste has a diverse number of uses. In many rural areas, Off-cut wood waste may be used by local schools for example, in craft classes, by factory employees and other associates as fuel, whilst machine waste is used in animal or poultry bedding, sold as pellets or briquettes, recycled into chipboard.

Wood waste has a diverse number of uses. In many rural areas, Off-cut wood waste may be used by local schools for example, in craft classes, by factory employees and other associates as fuel, whilst machine waste is used in animal or poultry bedding, sold as pellets or briquettes, recycled into chipboard.

Engineering waste out of the system is an important factor in creating a circular economy. Over the last few years the wood window sector in particular has seen a number of manufacturers working with their suppliers to standardise the range of sections required to make their respective windows. The resulting efficiencies have reduced waste in these instances to around 1%, compared to 25% using solid timber.

Timber’s environmentally friendly credentials also give it a significant advantage in circular economy terms over materials such as PVC-U, which does not harmlessly biodegrade. Global production of PVC-U window frames has been continuing to grow, with most PVC-U windows sold to domestic customers made from virgin (unrecycled) PVC-U.

Durable and innovative

In an uncertain and fast evolving world, versatility and durability are high priorities if a product or material is to become part of the circular economy.

Wood is a highly durable building material. Modern treatments mean that wood can resist biological degradation even longer, as well as locking in carbon. The long lasting nature of timber products makes them excellent value for money too. Properly maintained timber windows have in some instances lasted well over 100 years – the oldest surviving examples of sash windows were installed in the 17th Century at Ham House.

Wood is a highly durable building material. Modern treatments mean that wood can resist biological degradation even longer, as well as locking in carbon. The long lasting nature of timber products makes them excellent value for money too. Properly maintained timber windows have in some instances lasted well over 100 years – the oldest surviving examples of sash windows were installed in the 17th Century at Ham House.

A life cycle assessment report by the Wood Window Alliance showed that over a 60 year design life timber windows offer the lowest cost alternative for mild scenarios, while aluminium clad and modified timber offer lower whole life costs for moderate and severe scenarios. This compares to PVC-U windows which were shown to have the highest whole life costs over 60 years in all scenarios. This report from Heriot Watt University shows that the timber-based frames considered last longer, are better value and have significantly lower environmental impacts than comparable PVC-U frames.

Modern methods of construction mean that timber components can be pre-engineered off site and delivered ready to erect into a form or structure. This ensures that high levels of quality control are practised in the factory and that accurately manufactured components are assembled quickly and efficiently on site.

One example is the Stadthaus building in Hackney, London – formerly the world’s tallest residential timber structure. Apart from its concrete foundations, the nine-story residential tower is built entirely of cross laminated timber. Using timber in this form of construction meant that the project was completed in just 49 weeks compared to 72 weeks using the more traditional concrete and steel alternatives. On this occasion, timber’s thermal properties also meant that there was no need to install additional insulation.

Further reading on the Circular Economy:

Interactive Knowledge Resource for Circular thinking in Construction

Three Circular Economy myths excusing business inaction

Ellen MacArthur Foundation on the Circular Economy

The Great Recovery – redesigning the future

European Commission – Moving towards a circular economy